For some readers, the title of this article may sound bizarre, contradictory, or even plain nonsense. And that would be a normal response. By definition, why would a company specialized in digitalization and automation processes be preoccupied with anthropology?

What possible connection is there between a conjunction lacking syntactic function, a story about a wooden puppet, and a robot?

Furthermore, what interest would a science focused on studying the ‘human phenomenon’, in Claude Levi Strauss’ terms, possibly have in a field as non-human as Artificial Intelligence?

Before we can answer these questions, as legitimate as it may be, it’s important to make a few important remarks.

This article represents the materialization of the collaboration between Encora and Antropedia, the first of many in a long-term project – one of the few in our country – that will focus on the relationship between anthropology and technology, with emphasis on AI, machine learning, and Big Data.

Challenge: deploying one of anthropology’s classical missions in the field of artificial intelligence

Although the present article aims to be an introduction, it is also a challenge, that of seeing one of anthropology’s classical missions being deployed in AI’s theatre of operations, transforming the familiar into strange and the strange into familiar. A fitting way to broadly illustrate the way in which this process works is to put it in the context of a puzzle.

Each of us holds a piece of a puzzle that needs to be reconstructed in order to reveal, upon completion, the way things work: a family, a village, an organization, a society, or … artificial intelligence. The pieces which must be put together are built from practices, interests, and values that each actor uses to put into motion various basic social mechanisms. This type of deconstruction and reconstruction has become more present in the area of Science and Technology Studies (STS).

Moreover, anthropology has influenced STS so profoundly in the last few decades, that it is now difficult to make a distinction between the two. Science and Technology started by being considered a central and vital component of anthropological research, and ended up being absorbed in the discipline and even being included in the “Anthropology of Science and Technology” sub-category.

From this broad point of view, anthropologists started focusing on research labs, scientific discovery, technological transformation, technological production management, techno-policies, to list just a few areas, as well as towards the impact that they have on other actors.

On the other hand, the blurry effects of discovering these terrae novae could also be observed outside the academic domain, in the business area, where more and more global companies in IT have become interested in anthropological insight. This interest has lead the anthropologist Grant McCraken to invent the corporate position known as CCO (Chief Culture Officer), wherefrom, without claiming to offer magical solutions for any problem, anthropologists could attain a level of understanding that may elude an untrained eye and, more importantly, may go unnoticed by management.

Big Data and AI perspective

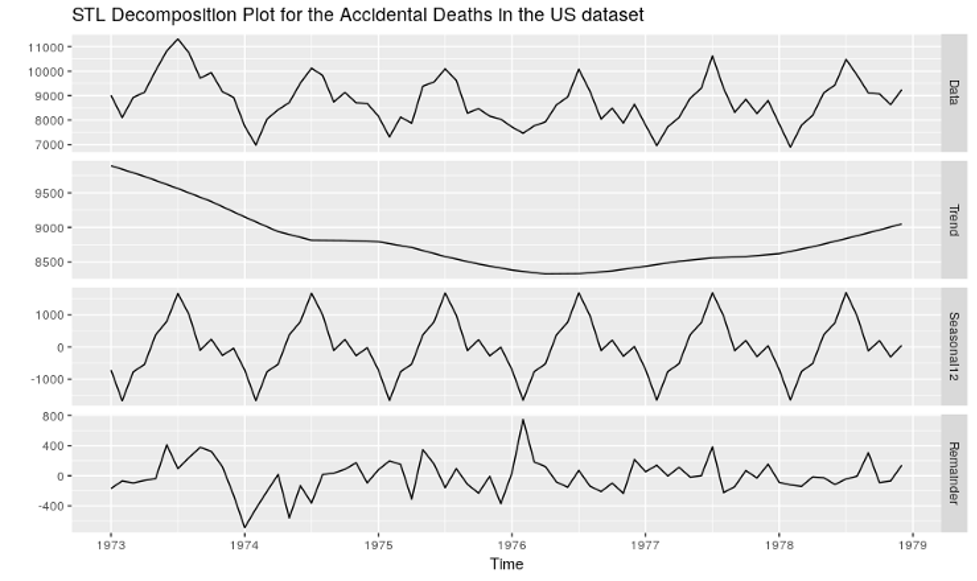

Focusing back on our own interest, anthropologists help with Big Data and AI efforts by supporting Data Scientists, balancing the stability of macro numbers with the fluidity of a multitude of micro connections, or, put another way, by complementing Big Data with what some anthropologists call Thick Data, following Clifford Geertz.

On the other hand, the accent put on the ethical dimension of this global process of nature quantification – transforming nature (animals, humans, plants) into data banks – as an essential part of machine learning algorithms, has the end goal of becoming a cornerstone element in building any data analysis software infrastructure. In short, in spite of all these new and innovative elements, the challenge for anthropologists when it comes to AI lies within the classic perspective, on a larger scale, of understanding and explaining alterity, discovering a new ‘other’.

If we zoom out, it can be said that AI is wrapped in a narrative that has its roots in humanity’s history. Stories about animate objects, which spring to life through human intervention, have followed us through time, in different forms, from our childhood all the way to maturity.

What is Pinocchio if not an intelligent robot who signals through the elongating of his nose errors and cognitive biases?

From its first publication in 1881 up until the very present, Pinocchio, C. Colodi’s story, the pseudonym under which Carlo Lorenzini published, has fascinated kids around the world, as well as adults. It is an interesting fact that the puppet created by Geppetto is a child because in the laboratories of MIT, and in various other places, robots are reimagined by researchers as being similar to children (Richardson 2015).

AI is like a small child that is learning

During a discussion I was having recently, my interlocutor illustrated the way AI works in the same way: It is like a small child that is learning. Researcher Kathleen Richardson (2015) revealed the profound ties that exist between AI, Robotics, and the psychologist Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. Even if the robot is not intentionally created as a child, it incorporates notions of infantile psychology development and epigenetic robotics.

But why compare AI to a child?

The short answer would be that this is the first step towards the development of relational models for non-humans and that this was structured especially around the creation of machines that can mime, imitate, and simulate the child-parent relationship. It is of no surprise that the theme of relational models was a trend that started simultaneously in anthropology and in robotics. And this is where the significance of the word “And” comes into play.

In a speech held in 2003 at an Anthropology Conference suggestively titled “And”, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro states that the little magic word “And” is for the universe of relationships that which the notion of “mana” (Melanesian concept that refers to supernatural life-giving power) is for the universe of substances. Thus, the functionality of “And” is not syntactical because it ties and creates relationships, has the potential of adding to the world while also diversifying it.

When the topic of AI is being discussed, this universe of relational models, as well as its process of becoming, should be kept in mind. As a consequence, following Jensen and Rodje (2010), the questions that we will try to answer are not just what something is, but also what AI transforms into or what it is capable of transforming into.

AI, an actor-network that bypasses its individual status

This accent on relationality, the importance of ‘and’ in such actions, is best highlighted in the theory of actor-network theory (ANT) which offers special attention to the relationships between humans and non-humans.

In this kind of methodologic and theoretic frame, AI is no longer cut and dry technology aimed at solving a single problem or extracting a pattern from a monumental volume of data, it is a collective that brings together different types of resources and interests, people, and technology, data science and statistic formulae, managers and management strategies or techniques, IT experts and experts of various other fields (insurance, urbanism, nutrition, etc) data engineers and product designers, marketing specialists, lawyers and sociologists or anthropologists, different types of material or immaterial technical infrastructure. The more diverse the network, the bigger the possibility that the value of the team will be reflected in an efficient strategy.

AI is therefore no longer just an actor, it is a network or better said an actor-network that bypasses its individual status and thus crossing over to the collective. Revealing this heterogenous network is the very aim of this editorial project, one in which anthropology can put its explanatory power in practice.

References

Jensen, Caspar Bruun and Kjetil Rödje, Eds. Deleuzian Intersections. Science, Technology, Anthropology. New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2010. Pp. 278.