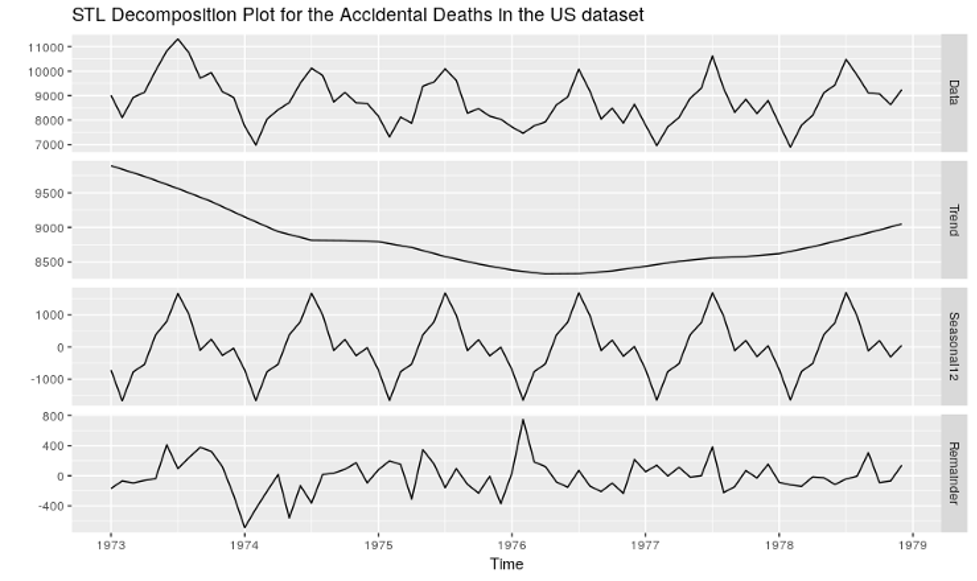

The plot

There is a lot of great public content on the internet about development processes, methodologies, frameworks, best practices, a.s.o. and I will not try to describe the same things again with different words. What I’ll be doing instead will be to present some of the real-life challenges we’ve had with software building activities in one of our recent projects and the solutions the team came up with, to improve the process.

The project, in a nutshell:

- Agile methodology – SCRUM;

- Phase 1 – MVP:

- Timeline: 6 months;

- Single team of 10 people (including PM serving as Scrum Master, developers and QA engineers);

- Phase 2 – full-feature:

- Timeline: 11 months;

- Two teams of 10-12 people each;

- Phase 3 – major integrations:

- Timeline: 11 months;

- 5-6 squads of up to 7 people each;

I will be covering the challenges we had in each project phase:

- trying to be agile and do SCRUM with “mid-sprint additions” and estimations in points;

- team size and coordination e.g. challenge of keeping everyone focused in a backlog refinement meeting with a big team vs. coordinating on intertwined functionality across teams and avoiding duplicate implementation;

- continuous integration (CI) and development workflows or “automate, so you don’t have to remember!”;

- continuously delivering tested software while working on no-go features at the same time thus avoiding code freeze;

Don’t try to get around SCRUM

One of the things you often hear about SCRUM is that if you get outside of the frameworks’ rules just for a bit, you’re not doing SCRUM at all. For example, “let’s skip stand-up just for today, because we have a lot to work on” or “we only have half an hour available for planning” or “we have already talked about everything, no need to retrospect”.

Things that we have struggled with:

- Estimating in points – there is an infinite discussion about what those points mean and the simplest idea to stick to is: “it’s just means that the team uses to track progress”. Some teams are using points, others are using t-shirt sizes, but eventually, it is just ‘something’ to use, to help track the team’s progress towards the sprint end against the work they’ve committed to. And even though it takes some time to reach estimates consistency, eventually the team should reach the “performing” state when everyone has created a good perception and understanding of what a point means and uses the system effectively, within the team.

- Mid-sprint additions (work added during the sprint) – for our project it seemed to be the natural way to build the application – we always had mid-sprint additions. But that is fine, as long as we respect the process: have the team estimate and re-commit (re-evaluate the sprint commitment, negotiating with the Product Owner , and de-prioritizing work if needed).

Things were very different between pre-MVP (before the first release) and post-MVP development cycles. In pre-MVP, we had a smaller team and it took a while to get the needed discipline. We redefined at least a few times the way we were estimating. The main pain point was not being able to hold to the sprint commitments, and that was caused mainly by poor estimations.

We tried reference stories, ideal hours, but eventually agreed to drop these constraints, created some guidelines about points per complexity, stick to points and Fibonacci numbers:

e.g. 1 point is something trivial that does not need investigation, 5 points is something that is complex, but can be handled by one developer in one sprint and 8 or more points needed to break down.

Later in the project, as the team grew and had to split it, we continued the process. But since the teams were already formed and naturally assembled, with developers aggregated based on personality compatibility, timezone, etc., the project’s complexity increased and the main challenge transformed from poor estimations to stories added in the middle of the sprint (mid-sprint additions), due to various reasons: unforeseen dependencies, user feedback that was critical to the business, production bugs, etc.

So the problem remained: we were not landing sprints. However, as soon as the team committed to maintaining the SCRUM principles and ensure full transparency e.g. re-prioritizing and labeling not-committed items based on the principle “add something, then pull out something else”, we quickly started to see good results. But then, with a growing team, a new kind of problem appeared: coordination. I’ll talk about this next.

Coordinating squads

A squad is just another name for a SCRUM team. When multiple teams are working on the same project, sooner or later they will have to coordinate on some functionality. In our case the initial two teams were working on the same code base, but for different functionalities of the project. However, even though each team had their own agenda, the teams shared a common goal: the next release.

Early on, it was challenging to keep everyone in sync. So this is what we did to address the problem:

- Shared planning meeting when we had two teams, but later decided to have each team with their own SCRUM process (shorter, more focused meetings) and started having once a week coordination meetings of Squad leads with Product Owners and Scrum Master(s) – to keep everyone in sync regarding scope and progress (SCRUM of SCRUMs).

- A typical problem we faced was duplication of code: one team needed to build a component for their feature, but the same component was needed by another team, which sometimes led to having that component developed twice. Obviously, this was less than optimal, on several levels. We’ve addressed this by creating a list of domain experts – people that had the best knowledge in certain areas of the application and have them give a pass on the implementation plan for features.

- Once-a-week guild meetings – technology focused 1-hour-meetings: one for frontend and one for backend (fullstack developers had to join both). In such meetings we discussed anything from code reviews to architectural changes, or new features implementation details, whenever someone needed a second opinion.

- Last, but most important in my opinion, since the team was widely distributed geographically, everyone encouraged over-communication: we made everyone in the team feel comfortable about reaching out to people and feeling encouraged to jump on a quick video call, whenever it was effective to do so, to figure things out.

The development process: focus on code quality

Continuing on the sprint-landing issues, even if we were “development ready” two days before the sprint ended, there was still not enough time to get the features in a “Done” state. This was because, on one hand, developers can make mistakes and code may have bugs, and on the other hand, there is often a bottleneck when features are tested by QA and need to have them accepted by Product Owners.

We focused on solving these issues by:

- Making sure that code quality reaching QA is good and well documented;

- Always prioritizing the full, complete delivery of features, over work in progress; always prioritize defects from QA for developed feature or pushing it to “upper” environments rather than focusing on the newly started feature;

Things that we set up to increase code quality:

- Mandatory code reviews which were requested publicly on a ‘dev’ Slack channel so that everyone can see changes and build knowledge.

- Code quality auto-checks:

- Linters blocking commits and pushing code;

- Code blocked from merging if unit tests didn’t pass;

- Code blocked from merging if not reviewed (core functionality required 2 reviews and 80% coverage);

- Non-blocking checks: branch name follows convention, commit message follows template, follows template;

- Code being “dev ready” when handing it over for review (tested in local environment against all Acceptance Criteria and instructions prepared for the reviewer to easily test the code in his/her own local environment if needed);

- Code being tested in the Dev testing environment by the developer (integrating with other devs work) before putting it up for testing by QA (owned by both developers and QA);

- Code is validated in the QA testing environment: although the QA testing environment is traditionally owned by the QA team, having the developer make a quick run of the feature before handing it over for testing is a good idea to discover things like forgotten configuration changes or missing merges of related code in other repositories.

The continuously shippable product setup

Things really started to become difficult when we transitioned from a once-in-a-while release to a continuously releasable solution. The former was a straightforward process that involved a code freeze before the release, testing, fixing for two days, and releasing. The code freeze was needed because after regression testing, all found bugs had to be validated in the lower environments first, but we didn’t want the validation to interfere with any work in progress. Since the releases were only once in a while, this flow was acceptable.

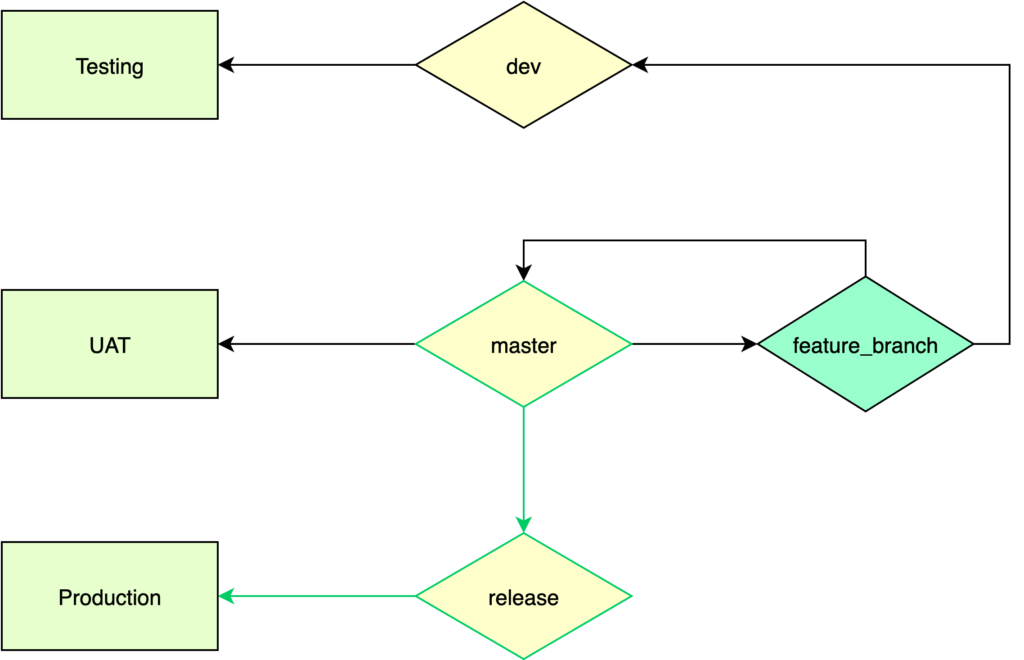

Here is a diagram showing the simple CI/CD pipeline initially used:

Developers created their feature branches from master (considered stable), tested the feature locally, merged it into dev which automatically deployed it into the Testing environment. Initial pass was done by developers (validating that it was integrated well with work from others and solving potential conflicts).

The QA team would then test the feature in the Testing environment and when validated, the feature branch would be merged by developers into the master (solving potential conflicts again) which would automatically deploy to UAT. At the end of the sprint, all features that got into the master branch were considered releasable (in green), and the code freeze began. If a bug was found, it would be treated just like any other feature.

Later on, when we started to release at the end of each sprint, code freeze was not an option anymore. Imagine at least two days of code freeze every sprint and half of the developers being blocked from integrating code from other developers. So we upgraded to a new process that allowed us to continuously work on features while being able to release Done features at any moment.

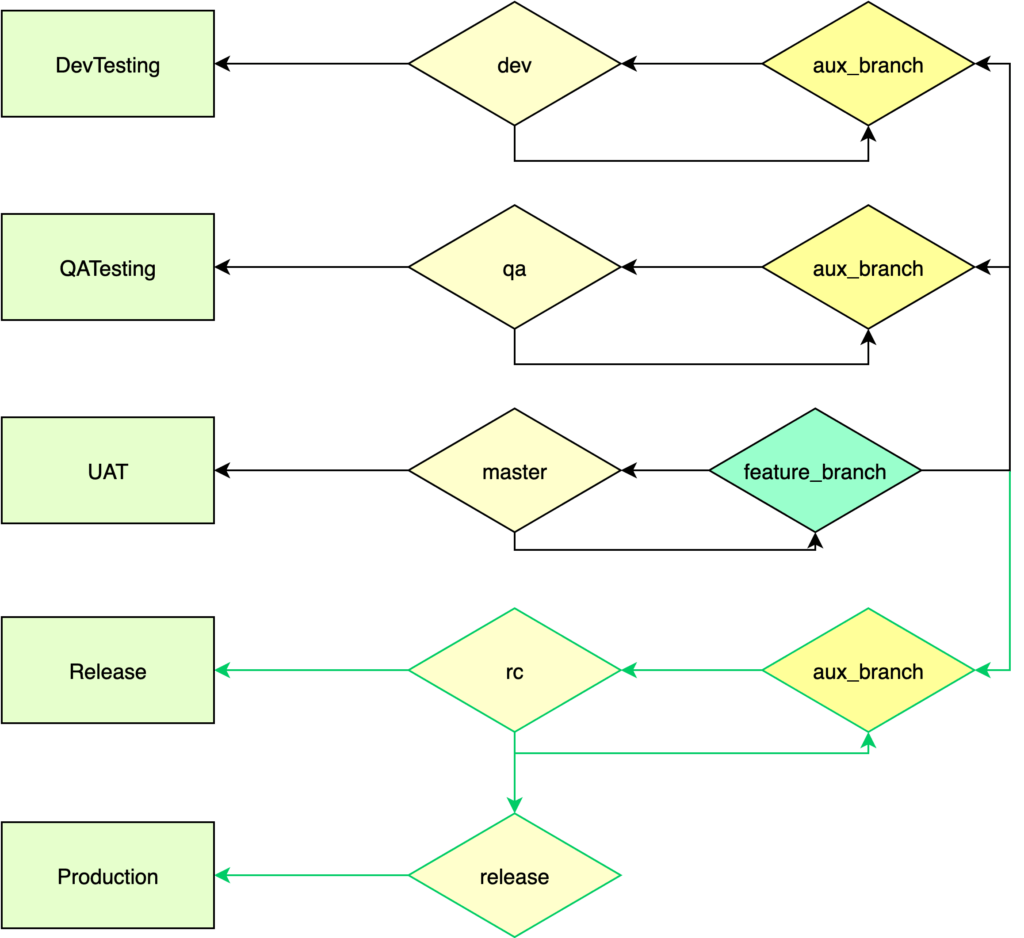

Here is a simplified diagram of what it looked like:

The environments:

- Local (on each developer’s machine);

- Dev Testing (deployed from dev branch and integrating work from other developers);

- QA Testing (managed by QA to get clean integrations of validated features of their choosing);

- UAT (validated by QA, but owned by Product Owners, used for accepting features);

- Release (pre-production environment, owned by Product Owners);

- Production;

So what happens in this diagram? The developer tests on both the local environment and Dev testing (ideally automation tests are updated as part of the local testing, which would cover much of the second testing phase), hands it over to the QA team which tests it in the QA testing environment.

When everything is approved by QA, code gets pushed to UAT for acceptance by Product Owners. After being accepted, the release manager will coordinate with Product Owners and stakeholders for the set of features to be delivered on the next release, building the Release environment with those. Once the release environment has been validated (for us it was always a joint effort by QA team and Product Owners), a Release in Production is scheduled.

One of the problems we had to solve was how to push independent features.

One thing we did was to make sure that the dev branch never gets merged in the master branch. Secondly, the master branch was the base for all feature branches. The Dev branch was considered “dirty”, meaning that it contained potentially harmful code, since it was not fully tested, as integrated with other code.

The Master branch would always get deployed to the UAT environment, by simply merging the feature branches into it.

With the other environments we had to take another approach in order to be able to control the code that gets in.

For example, for the QA Testing and Release (therefore implicitly for Production as well), we did a cherry-pick based approach with auxiliary branches.

Key takeaways

| 1. | SCRUM is here to help, not get in your way:

|

| 2. | Team alignment: have team members meet often (virtual meetings are okay) and organize public code reviews; |

| 3. | Aim for code quality by enforcing constraints and have strict development flows that are known and understood by everybody; |

| 4. | Automate as much as possible from QA to deployments, a.s.o.; |

| 5. | More flexible (loose) release processes lead to more complex flows. |